Posted by  Joshua Kiehl on Thursday, March 15, 2018

Joshua Kiehl on Thursday, March 15, 2018

As winter arrives, bringing with it ice and snow, historic building owners are faced with the additional challenge of keeping walkways and steps around their facilities safe for pedestrians and clear of slipping hazards. Safety is always paramount, but long-term damage to historic masonry buildings from de-icing salts, doesn’t need to be a tradeoff.

In my historic architecture restoration work, I’ve seen a lot of this type of damage that could have been avoided, along with the subsequent restoration costs. I hope that by understanding the available products and best practices specific to de-icing near historic masonry, damage can be mitigated or eliminated; preserving our built heritage.

what's the problem with de-icing salts?

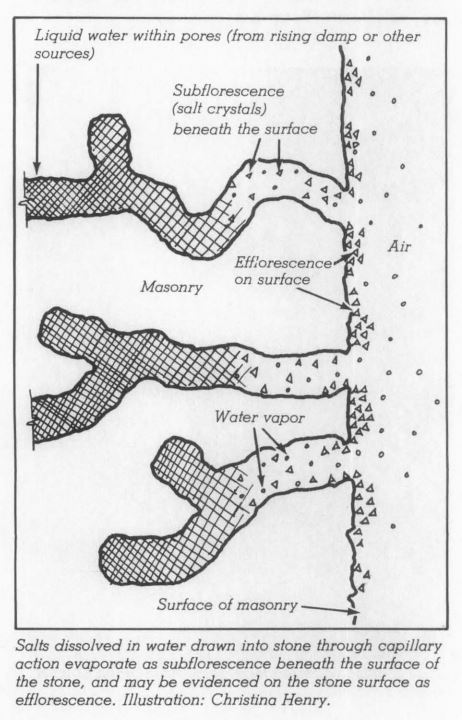

Problems caused by de-icing salts occur when the salts are absorbed into masonry building surfaces adjacent to the areas (like walkways) being treated. When the ice/snow melts the water-soluble salts can wick up into the lower portions of the masonry wall.

Absorption of salt by the masonry can lead to subflorescence, a buildup of salts below the masonry surface. (Surface accumulation of salts on the masonry is referred to as efflorescence and can be indicative of salt accumulation within the masonry). An increase in salt concentrations can result in pressure, especially during freeze thaw cycles, leading to spalling or delamination at the face of the masonry. De-icing salts can also cause salt fretting (etching) of stone surfaces and corrosion of metal building materials located near the base of walls, including: wall flashings, handrails and other decorative metal elements.

compounding the problem...

Older masonry structures that have been mistakenly re-pointed with hard cement mortars have an even greater risk of damage resulting from salt deposits. Prior to the 1930's many masonry buildings were constructed using lime based mortars which have lower compressive strength and greater vapor permeability than most modern Portland cement mortars. The characteristics of lime based mortars are important to the performance of the wall as they allow stresses in the masonry (expansion, contraction, moisture migration, etc.) to be relieved in the mortar joint rather than in the masonry units. In buildings that have been repointed with harder, less permeable Portland cement mortars these stresses (which are exacerbated by the presence of soluble salts) are transferred to masonry units often resulting in accelerated spalling and delamination of the masonry.

Similar problems can result when older mass masonry walls have been coated with water repellents or sealers. Many of these products prevent masonry from drying out and allowing entrapped water to evaporate. Resulting build-up of moisture in the wall can result in damage to the masonry units during freeze thaw cycles which, as noted above, can be exacerbated in the presence of salts in the masonry. Generally we do not recommend these products for historic masonry applications.

de-icing salt options for your historic masonry building

As you learned above, de-icing salts can be quite harmful to historic masonry. But, sometimes they are necessary. Selecting and applying the appropriate de-icing salt, requires (1) understanding the de-icing salt options and chemical properties, and (2) understanding your building's construction and materials. We can look at the first half of that equation with some help from the New York Landmarks Conservancy (NYLC).

The NYLC, a preservation organization based in Manhattan, provides some helpful information on their website regarding de-icing salts and ways to avoid or minimize salt related damage to concrete, which is also directly applicable to historic masonry structures. Here is a summary of the four primary de-icing salts used for ice and snow removal they provide:

Sodium Chloride (NaCl)

Also known as rock salt, is the most common deicing salt. Rock salt releases the highest amount of chloride when it dissolves. Chloride can damage concrete and metal. It also can pollute streams, rivers and lakes. It should be avoided.

Calcium Chloride (CaCl2)

It comes in the form of rounded white pellets. It can cause skin irritation if your hands are moist when handling it. Concentrations of calcium chloride can chemically attack concrete.

Potassium Chloride (KCl)

Is not a skin irritant and does not harm vegetation. It only melts ice when the air temperature is above 15 F. When combined with other chemicals it can melt ice at lower temperatures. It is a good choice.

Magnesium Chloride (MgCl2)

Is the newest deicing salt. It continues to melt snow and ice until the temperature reaches -13 F. The salt releases 40% less chloride into the environment that either rock salt or calcium chloride. It is far less damaging to concrete and plants. It is the best choice.

best practices for de-icing near your historic masonry buildings

- The best practice would be to not use a de-icing salt near your historic masonry. If that is not practical, we recommend magnesium chloride, since it releases the least amount of harmful chloride. Use it sparingly and as far from your building as possible.

- Always remove as much snow and ice manually before applying any de-icing salt.

- Supplement de-icing salt with sand for added traction.

- After the danger of freezing temperatures subside, clean up treated areas thoroughly by sweeping up and rinsing with water as soon as possible.

- Communicate! Many times other departments or outside contractors are used for snow and ice removal. Make sure they know your plan and deploy the strategy and materials you’ve identified.

For more information on historic masonry buildings and their care please feel free to contact us, post your questions below, or connect with me on LinkedIN.

contact us join enews

Categories: Buildings & Campus

Tagged: Architectural | Historic Preservation